Kwibuka24

By Jo Ingabire Moys

Lately I have been thinking about legacies. What kind of legacy will I leave behind for my children?

Will I be remembered, and if so, for what? I hope it’s for great deeds. I can’t yet conceive but I suspect monuments to my success will be cold comforts for those I leave behind.

I hardly remember my father’s achievements, although they were many. The lands and houses he left are testament to his hard work and brilliance, but they tell me nothing of the man he was. I’m told he was studious, but what kind of books did he like? Did he like nature or prefer the city? What kind of prayers did he whisper in Mass?

My brother, Julius, was killed aged 13 and was denied to chance to show the world what he could do. There will be no statues erected in his praise. Even his body was lost when his remains were scattered across the land; if there was no proof he’d died, there would be no evidence that he was murdered.

The football-mad boy who trained the dog to chew Dad’s shoes on command. That is worth remembering. He was not just a faceless African victim in another African tribal war. His compassion for all living things, the purity of his soul, his perfect comic timing – these are greatly missed.

A son, a brother, a friend; his short life deserves to be commemorated, to be celebrated.

Today we remember our loved ones not for what they did but because of who they were. Fathers, mothers, brothers, sisters, friends and neighbours. Victims of senseless violence, discrimination and oppression. Their lives mattered, they were important, we honour their memory.

Jo Ingabire Moys, Survivors of the Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda, Co-Founder, Memory and Documentation Officer

Survivors Tribune

Why remembering the Holocaust and subsequent Genocides shouldn’t be confined to one day only.

By Emma Bayley Melendez, Youth and Community Outreach Officer for Survivors Tribune

Holocaust Memorial Day only comes around once a year on the 27th January but for me the significance and importance of remembering the Holocaust and subsequent Genocides shouldn’t be confined to one day. Being a Youth and Community Outreach Officer, shows a commitment to keeping the testimonies of those who have been the victim of such atrocities in people’s minds. I have been planning an event for Holocaust Memorial Day and this for me is a way to educate people through the power of words. Education is one of best ways to prevent atrocities, when we learn about other people’s cultures, religious beliefs and heritages we realise that our differences should be celebrated as opposed to being used against us.

Genocide survivors’ stories are so incredibly useful, as tools to help us understand periods of time where such atrocities have taken place. It is much easier to relate to individual testimonies, through listening to an individual’s testimony we can humanise the large statistics that are used to highlight the scale of a genocide or holocaust. When I visited Auschwitz, and saw an exhibit which had a wall full of photos of only a tiny proportion of those affected by the Holocaust I remember finding a photo that I would mentally bring back with me when I came back to England. Even though I visited early in 2016, I can still vividly remember this photo.

I hope to develop my role in the future by working closely with Survivors Tribune to deliver talks to younger audiences. This will be incredibly beneficial, whilst genocides and holocausts are naturally sensitive topics to discuss with audiences; I believe it is fundamental to do so to ensure that people are informed enough to speak out against present and future atrocities.

As George Santayana said, “those who do not remember the past are condemned to repeat it”. For me this is very true and the reason that I have been proactive in engaging with Holocaust education through working with organisations such as Holocaust Memorial Day Trust and Survivors Tribune is because of how dangerous it is to forget the past. Through such organisations I have met many inspiring individuals who have such varied experiences of such atrocities, as a result I have become more informed and have a greater desire to ensure that everyone is educated on these human rights crises that are still taking place in society.

Education about genocide: Lessons from Rwanda

By Jo Ingabire Moys

“As a genocide survivor, what do you think about ongoing persecution in Myanmar or the rise of anti-immigrant feeling in the West?”

I had just given a talk to an assembly of secondary school students when a history teacher asked me that question. Taken aback, I muttered, ‘I don’t know.’

Instantly the tension in the room dissolved. The students, who had clung to every word in my story of dodging bullets across hilltops and sleeping in ditches to hide from bloodthirsty militia. Now they began checking their phones, others chatting and giggling with their friends.

The disappointment on the teacher’s face was all too apparent. It seemed that I had missed my cue for a teaching moment on current affairs and the students, having listened to my testimony, had filed it under ‘just another history lesson’ and now the present beckoned.

Frankly, this seemed a reasonable approach to looking at genocide, especially to me as a survivor. I told my best friend from university that I had been in Rwanda in 1994 on the last day of our three-year degree. At first he thought it was a terrible joke, then horror, pity and curiosity washed across his face at once. He didn’t know if or what he could ask.

That kind of information changes a friendship. I had known this to be the case since I was 5. After my father and siblings were shot by local police officers whilst our neighbours watched from their windows, my mother knew that we if we were to survive we had to move. And so,we moved to hide from anyone who knew us because our names were on a list; we couldn’t be known as victims.

Occasionally the gunshot wounds in our limbs would betray us and we would move again. That’s how we lived throughout the 100 days of the genocide against the Tutsis.

I had mastered this lesson by the time I was a teenager living in London. The posturing was almost always about identity. I pretended to be Burundian when the movie Hotel Rwanda came out to avoid those curious glances and probing questions – questionsI didn’t what to contemplate let alone answer.

And yet, still, they followed me. In the age of Brexit, #MeToo, Libyan slave markets, natural disasters, the Refugee crisis, travel bans, ISIS, the Yazidi genocide and Rohingya ethnic cleansing it is difficult to determine which headline should bother you the most. I chose to disconnect, like many. Compassion fatigue is especially weighty when you can relate to the suffering of the people featured in morally questionable ‘charity porn’ adverts.

I admit that I have been burying my head in the sand and hoping that the promise ‘Never Again’, made to Holocaust and genocide survivors would be fulfilled.

I live in a peaceful nation where I experience little to no discrimination, so, to a large degree I have lived to see the fruit of that promise. What I didn’t consider was that although I had outgrown my fear of being identified as a victim, I wasn’t immune to an oppressor’s mind-set. It begins with apathy, a ‘them and us’ perspective, and subtle collaboration.

Divisive language and campaign promises soon become propaganda;minorities and immigrants become scapegoats for unstable economies. Slowly it makes sense, we believe it, we are seduced.The only cure to this an alternative voice.

There will always be people who wilfully chose hatred but for the undecided or uninformed a counter-cultural narrative is needed.

The international community or governments aren’t renowned for being on the right side of history as was the case in Rwanda, Sudan, and Syria and now in Myanmar.

There is hope, however in the average man’s kindness. The #LoveAmy Campaign raised a million dollars in a day to help the Rohingya people. Comic Relief’s 2017 funding raising campaign has broken records by raising over £75m. Hundreds of people welcomed Syrian refugees in their own homes because it was the decent thing to do.

Education in all sectors is a vital voice, uninfected by media hysteria, fake news and sensation headlines. A grassroots movement called the iDebate in Rwanda set up by student, Jean-Michel Habineza, allowed debaters to air and confront their parents’ prejudices. Children of survivors freely talked to children of perpetrators, forming their own opinions untarnished by decades of offences and conflict.

Standing on that education platform publically sharing a story that opposes genocide revisionist theory, I saw the students captivated by the truth.

It humanises, connects, teaches but also empowers. It demonstrates that we can choose to affect change positively even if in small measures.

The task of challenging extremist ideology is for all humankind because it ultimately affects us all, but it begins with personal responsibility. There are no glib answers to the big issues affecting society, but we can and must all take part in bringing solutions, however small.

Listening out for different voices, learning about shared values, and valuing our human rights and other people’s is one way we can honour the memory of victims of genocide and promise future generations, ‘Never Again’.

Jo Ingabire is a Film and TV professional based in London, survivor of 1994 genocide against the Tutsi and co-founder of Survivors Tribune a global educational initiative established by survivors of the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda, drawing on their own first-hand experiences to make a stand against discrimination and genocide denial, promote reconciliation and forgiveness. ST enables survivors of modern genocides and other global conflicts to share their experiences through public speaking events in schools, colleges, and universities.

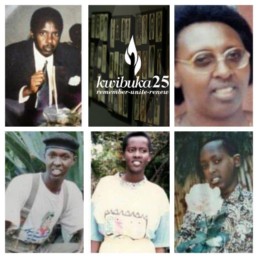

SOUVENIR: And Homage/Tribute to the Comrade Jimmy Karambizi.

By Rwigema Seka Emery

It was during this period of spring, twenty five years ago, in the hills of Byumba, when you and I first got to know each other, both part of a rebellion movement fighting to liberate our home nation.

I will always remember those comrades who died on the battlefield, in particular you, dear Jimmy Karambizi, because you were one of my battlefield friends who supported me most when I needed it.

We, who have had the grace to survive, sing "Wawili wakufe watatu wapone waliobaki watajenga Rwanda – if two dies three will survive and those who will survive shall go on to liberate and rebuild our nation.” We give you today a vibrant tribute. Just to let you know, in memory of your sacrifices our country has given you two medals: one for liberation, and the other for having stopped the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi in 1994 in Rwanda.

Dear comrade, I’m testifying today because your sister, Carine Karambizi, the only survivor from your family, has asked me to do so, but I don’t know where to start because I can’t find the right words. I am trying to reflect and to think because I have the obligation to tell your story to her, an obligation of sharing the memories of all my comrades who died at the battlefield, but your memories in particular are troubling me most because we talked so much about your family.

Comrade, I can’t find the right words to describe your courage, determination and love for your country, to which you never hesitated to give your blood. Dear comrade, I just want to tell you that you did not die in vain because the Genocide against the Tutsi was stopped and thanks to your sacrifice today we live in a country full of peace and prosperity.

We had many difficult times. On a number of days we had to dodge bullets which flew over our heads and took cover from bombs that were falling on us. So many comrades lost their lives on the battlefield and many others were seriously injured. Whenever there was a ceasefire, it was always the best moment, because you and I had the chance to bond and get to know each other better, and learn more about your lovely family whom I had never met.

I would have liked you to be here among us but hey, when you left us I thought the chapter was close and there was no any other chance of reunion! And here again your shadow reappears through your only surviving sister, who continues to testify and keep the memories of her family alive through her descendants until the end of time.

I have the firm conviction that your soul rests in peace because the scriptures tell us that there is no greater love than to lay down one's life for one's brothers!

To you Carine Karamibizi, Comrade Jimmy Karambizi of the 21st Infantry Battalion died in battle, attempting to repel three divisions of enemies from Kibungo, who were attempting to storm Kigali. Your brother fought valiantly and left his life there twenty three years ago in 1994.

I had the privilege of living with your brother in the rebellion fronts of Byumba, Mukarange, Gasambya, Rushaki, Kiyombe, Cyanika, Bwisige, and Kaniga. He was a young man who went to the battle with pride, courage and determination, thinking of the injustices and discrimination to which he was subjected. The Commander in charge of the mines in our company, he was first in line to take responsibility for de-mining: a perilous task.

When I think of my comrades I met in the first days of our liberation war, those beautiful/great, idealistic young men who died on the front, their images never cease to reappear, especially when I meet with their relatives and friends. This impression, I feel it every day, seeing your sister Carine Karambizi and every year in April when she commemorates our loved ones slain in the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsi, she always puts your picture in “Mukotanyi's uniform”; I thank her and I admire her courage.

Dear Jimmy, do you remember the promise you made us the last time we saw each other, giving us an appointment to meet at Kigali nightclub? You may be interested in finding out that I went there in your memory once we liberated Kigali. I was with your brothers-in-arms Zeus and Eric, and as we danced we talked about you, your bravery, your love of the country and your friendship. May the land of your ancestors be sweet and light. You can be proud of where you are because, thanks to you, those who hoped to annihilate an entire ethnic group have failed in their plans and today a new generation has seen the day for all those survivors of the genocide perpetrated against the Tutsis. RIP Commander Jimmy Karambizi.

The best stories I know about Jimmy Karambizi concern his most dangerous and risky missions, mining and demining territories wherever we were fighting. A young man of talent and discipline, he quickly acquired responsibility by being a very young commander. Of course, while Jimmy was the youngest of my comrades, he was the only one I knew who was fluent in the language of Moliere/French. Our friendship had grown over the years. He was a naturally good man, full of love and humour.

Being far from our families and friends, we used to talk about our family lives a lot and also our future plans, as the final destination was Kigali, and Jimmy was the best equipped person to tell us about life there, its beautiful girls and the best places for leisure and fun.

He loved to entrust us who dreamed of Kigali with beautiful pictures of his sisters, his cousins and friends, promising us beautiful girls once we were there —hey, we were young, and full of dreams of the future! Some of these girls came to Mulindi at the fundraising in 1993; it was the thunderbolt, the joy and the promise to see us again! We were overwhelmed as they say, since every day we were afraid of dying, fearful of not seeing these beautiful creatures again.

The sad story, dear Comrade Jimmy, is that what we feared turned out to be a reality. Those beautiful girls of Kigali whom you had promised us were all massacred for the simple reason that they were beautiful and Tutsi. On this spring of April, I commemorate and remember them through this testimony about you. Comrade Jimmy, I will never forget how many times I was in trouble with my superiors because I did not want to hand over my photo albums filled with pictures of the beautiful girls of Kigali. However, as we advanced on the fronts of Nyamirambo, the chances of finding them alive were diminishing day by day, because all the survivors that we were able to save in Nyamirambo kept telling us that all were massacred every time I gave them the names of the families. Later, I learned that your sister Carine Karambizi survived.

Allow me, Carine, to speak in the plural because your brother for us was a star; he was very much appreciated and had many friends, including myself. We knew the names of all the girls in Kigali and as soon as we arrived with pictures in our hands, I asked if anyone knew the Karambizi family: Olive, Carine and Yvonne Shamukiga and so many others, but unfortunately the answer was often disastrous. None of our future ladies survived the Genocide apart from the miraculous Carine Karambizi.

Thanks to the insistence of your sister Carine Karambizi, knowing well that you could have left acts of bravery from which many men could draw heroic serenity, it is my duty to testify to yours: your admirable qualities of simplicity, faith, valour, self-sacrifice and patriotism that make Rwanda proud.

And here, Rwanda as it is today was built by the sacrifices of the valiant fighters of whom I have the honour to praise one, the person of Jimmy Karambizi, whose heroism will be immortalised on"K'Umunsi w'Intwari – Heroes Day".

Thank you.

Rwigema Seka Emery, your Comrade of 21st Infantry Battalion. –

Translated in English by Eric Murangwa Eugene an old friend of Jimmy Karambizi’s and his family.

Genocide education has made a profound impact on me

By James Ingram, ST Youth Ambassador Coordinator

Today is Holocaust Memorial Day, where the UK comes together to remember the victims of the Holocaust and subsequent genocides. It also encourages us to reflect and try to learn from genocide and mistakes that were made. As a previous member of the Genocide 80Twenty group and an activist within the genocide education community, I know how powerful this process can be but also where improvements must be made.

Genocide education has made a profound impact on me. Prior to my involvement within genocide education I knew little about genocide. I knew the basics of the Holocaust and the names of subsequent genocide but I treated them as isolated moments of history rather than events that teach us important lessons. Subsequent to my involvement with Genocide 80Twenty, speaking to survivors from varying genocides and visiting Rwanda last summer, I now know how important it is.

Genocide education is more important than ever before. The world is faced with growing extremism, nationalism and xenophobia. Genocide education encourages young people to deal with these threats, teaching them about how society unravels and why we have to unify as people rather than divide.

Holocaust Memorial Day is also a day where we should recognise the contribution that survivors make. Survivors from groups like Survivors Tribune travel the country, often telling difficult stories. They sacrifice their time and energy to help create a new generation of young people that embraces diversity and feels morally responsible to prevent genocide happening again.

Yet work must be done to ensure that genocide education is the best it can be. Greater focus must be placed on positive actors in genocide. I was inspired to become active in genocide education not by knowing the details of the Final Solution but by watching Schindler’s list and meeting figures such as Carl Wilkens and Eric Murangwa. Genocide education must not be done to meet targets, it must aim to encourage young people to create a more inclusive society whether that is being involved in genocide education or just volunteering in the local community.

More opportunities must also be provided to young people to act upon lessons they have learnt from genocide education. Often young people feel inspired to act but have no vehicle to do so. This is why I will be heading up an Ambassador scheme for Survivors Tribune. Its purpose will be to provide an opportunity for young people who want to get involved with genocide education and shape it alongside survivors to make it the best it can be.

So today on Holocaust Memorial Day we should reflect on the lessons of the genocide, recognise the importance of education on genocide and renew the commitment to make sure young people get the best possible experience from it.

James Ingram, 18 years old. Original member and student leader of Genocide 80Twenty which began in November 2014 and I left this year as I have gone to university.

Learning Kinyarwanda helped me fall in love with my country, Rwanda

By Junior Sabena Mutabazi,

Not a lot of people can say their grandmother is their hero and role model but, I can and I do. Like many Rwandans, I was born outside my country, in a Bantu environment where languages were in abundant supply. I remember as a child at my school; if I turned left to a friend, I would speak one language, and if I turned right, I would speak an entirely different language - it was like the Olympics. But, neither of these languages were my mother-tongue, Kinyarwanda.

However, that was at school. At home, after my grandmother had noticed that my brother and I could speak several languages except Kinyarwanda, she passed an in-house ‘law’: Kinyarwanda was to be spoken at all times. At first, my older brother and I thought that we were being punished through no fault of our own; besides, how were we expected to communicate in a language we barely knew? It was a nightmare. In fact, many evenings we remained silent, we did not have a starting point to a conversation. The only way we could find solace was to read books or watch television – all of which were in English.

Thankfully, children are quick learners; gradually, as our grandmother taught us a few words and also made us listen to evening bulletins on Radio Muhabura every night, we also picked up a few words from here and there – in exile, Rwandans were everywhere. So, as a routine, my brother and I would go to school, speak English as well as other languages but, when we got through the front door and inside our home, Kinyarwanda lessons would be in motion, immediately. And after a few years of practice, my brother and I graduated as elementary Kinyarwanda speakers, certified by none other than my grandmother. There was no ceremony, but the reward was the ability to comfortably initiate a conversation and, even strike a joke! I was content with that.

In early 1995, a few months after the Rwanda Patriotic Front / Army had put an end to the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsi, my brother and I wanted to visit our motherland for the first time. However, before we could set off in the company of a relative, I remember my grandmother holding my hand and telling me: “Junior, when you visit your motherland for the first time, you will also be able to speak your mother tongue. I taught you and your brother Kinyarwanda so that one day, when you return home, those who exiled our people back in 1959 can hear you and other young Rwandans speak Kinyarwanda. When they do, from wherever they will be, they will realise that back then when they looted and burned our homes, killed our families, and drove us into exile, they may have succeeded at breaking our bodies, but they never ever succeeded at breaking our Rwandan spirit. Our culture, language, and traditions remained intact.”

Today, I speak more than four languages including Kinyarwanda. For me, if there is one single factor that can help explain why I have fallen in love with my country time and again, it is the ability to speak my mother tongue. This ability to speak Kinyarwanda, even though I have spent most of my life outside Rwanda, helps me to recognise and give value to my Rwandan identity. It helps me to connect with my people both at home and abroad, and it helps me maintain my culture as well as my heritage. The ability to speak Kinyarwanda has also helped me to maintain important links to family.

Looking forward, I also know that when I eventually decide to return home, Kinyarwanda will be an asset when I look to create or seek employment and even settle in a local community.

Many years ago as a child, I was none the wiser when it came to truly understanding why my grandmother was very strict with me and my brother. I did not fully appreciate the value of speaking my mother-tongue in a foreign country - it was irrelevant in my school life and much of my child life. And besides, I would have triggered the mockery of calling me a foreigner, even though I was nothing but. I found English to be the safest possible language. It was foreign, yes, but it was a colonial language, and we Africans place no stigma on foreign languages as long as they are the native languages of our former colonial masters. Instead, we tend to elevate whoever speaks the most in our societies. But, that’s a story for another day.

Fortunately, my grandmother was there to help me recognise the true value of speaking Kinyarwanda. Now, I am aware that most of the rationale behind speaking Kinyarwanda cannot be linked to monetary value, but for me, there is more to monetary value. There is culture, heritage, history, education, and many more reasons why one’s native language is so important.

Today, from where I am in the diaspora, I know many other people, young as well as old, who wish they had someone of the same resilience and vision as my grandmother to help them or inspire them to connect or reconnect with Rwanda. For me, it was Kinyarwanda back when I was a kid. For you, it could be something entirely different or, the same. But, whatever it is, discover it and, run with it. You will be glad you did.

All things considered, I am not promising smooth sailing journey. Of course, there will be challenges. But, inaction should not be an option. In fact, I am reminded of Dr Martin Luther King who once said that - if you can’t fly then run, if you can’t run then walk, if you can’t walk then crawl, but whatever you do, you have to keep moving forward. I am forever thankful to my grandmother for the gift of Kinyarwanda!

Email: junior.mutabazi@yahoo.co.uk

Twitter:@Jsabex

Why do we remember?

By JO Ingabire Moys,

Why do we remember? Why does our history matter? I often hear of tales of elderly folk on their deathbeds looking back on their lives searching for memories that will say, ‘My life mattered.’If our memories are the sum of our human experience, how can victims of crime and genocide find meaning beyond their trauma?

I’m not thirty yet but for most of my short life I was defined defined by a singular event that has shaped my personality, my approach to social interaction,my entire worldview. This is not uncommon for people like me, Rwandans affected by the genocide against the Tutsis. In a matter of three months, a nation was changed beyond recognition by mass murder of a people group by their own government. That kind of violence registers not just on the nation’s psyche but on it’s soul. And yet every April, Rwandans take week out of their calendar to remember.

In September 2015, the United Nations General Assembly established 9 December as the International Day of Commemoration and Dignity of the Victims of the Crime of Genocide and of the Prevention of this Crime.

Personally, I think remembering for the victim cannot only be therapeutic, but it is essential in constructing an identity beyond the trauma. By acknowledging the hurt endured, there can be healing. In facing and confronting your persecutors, there’s justice and dignity to be found. The word ‘victim’ often carries negative connotations and unnecessarily so. When it comes to issues of genocide where a people are systematically persecuted, it is vital to acknowledge their plight. When they are silenced, brutalized, oppressed, an essential part of restoring dignity is to address the manner of their persecution and create forums where their voices can be heard again and their stories told.

It is important to remember the perished and with living victims, to look back at their memories and say, ‘Your life mattered.’ Commemoration goes beyond learning from an event in history. It begins the process of writing history free of war and genocide.

Personally, I think remembering for the victim cannot only be therapeutic, but it is essential in constructing an identity beyond the trauma. By acknowledging the hurt endured, there can be healing. In facing and confronting your persecutors, there’s justice and dignity to be found. The word ‘victim’ often carries negative connotations and unnecessarily so. When it comes to issues of genocide where a people are systematically persecuted, it is vital to acknowledge their plight. When they are silenced, brutalized, oppressed, an essential part of restoring dignity is to address the manner of their persecution and create forums where their voices can be heard again and their stories told.

It is important to remember the perished and with living victims, to look back at their memories and say, ‘Your life mattered.’ Commemoration goes beyond learning from an event in history. It begins the process of writing history free of war and genocide.

Previous

Next

Learning Kinyarwanda helped me fall in love with my...

Return to site