100 RWANDAN STORIES

100 Stories for 100 Days offers carefully-curated sensitive insights into people’s experiences of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda. Focussing on moments of transformation and reflection, the stories explore a range of perspectives: those of survivors, of Tutsis outside of the country in 1994, of bystanders, perpetrators and visitors to Rwanda.

The 100 Stories project is being lead by genocide survivor and Ishami trustee, Jo Ingabire in collaboration with playwright and advisory board member Adam Usden.

PILOT PHASE

Following funding from the Arts Council, Jo and Adam travelled to Rwanda to collect the first thirty stories for the collection in Spring/Summer 2018. They were assisted by Gael Rutimbesa and Odile Gakire Katesi.

These stories will be available online later this year.

HOW WILL THESE STORIES MAKE A DIFFERENCE?

Accounts of the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi in Rwanda usually take the form of chronological narratives (before, during and after), often collected and edited by outsider interviewers and editors.

This project is different for two reasons. Firstly, instead of focussing on what happened it explores particular moments of emotional change and reflection. Secondly, it aims to foreground the Rwandan voices involved and make transparent the process of production – it is lead by a survivor, in collaboration with Rwandan writers.

Ultimately the 100 Stories will give readers a glimpse into people’s lives, an insight into our common humanity, a new way of approaching and remembering the past.

Eric Murinzi

I was born two months premature.

My mum was pregnant with me in 1993. My dad used to drive trucks from Rwanda to Nairobi, Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania. The Government at that time said he was a spy, so soldiers came to our home to capture him.

He found out in time and ran away to join the RPF in Uganda. My mum was left at home.

One night the soldiers came and found her alone. They asked her, “Where is your husband?” She told them she didn’t know. They asked where her other children were and she told them she’d sent them to the village. “No, you are lying,” they said, and started beating her up.

When they were beating her she started feeling pains. They said to her, “so you want to give birth to a snake? Let’s help you.”

They took a knife, they cut her and they pulled me out.

They left, thinking that we were going to die. The old woman next door, a Hutu, heard screaming in our house. After the soldiers left she came and took us both to the hospital. My mum stayed in hospital but the old woman took me back to her home. The genocide started at that point.

*

I stayed with that old woman during the genocide, in Remera, near the stadium. People would see me with her and she would tell them, “This is my grandson.”

I used to go and visit her after the genocide. She was still living in the same place and so was my family. My brother Yuhi was killed during the genocide but my elder sister survived.

One day I came home from school and found out the old woman had died. That was in 2006.

I went to her place and cried a lot, like she was my mum.

What I hear from people is that her children are in prison now because they were Interahamwe. I don’t know them personally.

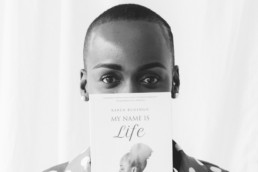

Karen Bugingo

Growing up in a post-genocide generation, you hear a lot of different stories and every story is worse than the one you’ve just heard.

I grew up thinking that Rwandans were the strongest-hearted people. People talk about how their entire families were wiped out, or how someone had ten children and now they only have two. I spent my childhood wondering how those people move on from that. Every Kwibuka, I’m stunned.

How are these people still living their lives?

I really don’t understand. I feel like an outsider looking in.

My grandma tells me that when we fled we saw many dead bodies, but I was only two years old. I don’t remember anything. My own life story sounds just like that – like a story.

My body was physically in Rwanda, but emotionally I don’t connect.

Quite honestly I don’t miss my parents. You can’t miss people you don’t remember. I honour their memory by listening to stories about how they loved each other but I’m never sad because I never felt their absence.

My grandma made sure we went to the best schools, we never lacked for anything. I lived a very normal, happy life. I realise how blessed I am to have been adopted by my own family.

When I was younger, I felt guilty that I was not struggling like the other genocide orphans. In high school we had a support group for genocide orphans and survivors but I didn’t feel as though I belonged with them. I mean, what would I have to say to them?

I don’t think your whole being should be judged by what your past holds.

As a Rwandan I’m much more than an experience connected to genocide. It happened, yes, but can we just move on? Surely there is a way to talk about Rwanda without focusing on the genocide. At the very least you can add other nice things about Rwanda into the conversation. We are a people who have been to hell and bounced back, we are that strong.

I was diagnosed with cancer when I was 19. I wrote a book about what I was going through, to find my voice in the midst of that chaos. It’s my story of hope and courage, which, I think, reflects the history of my country.

It’s called My Name is Life.

Mussa Uwitonze

I am holding tight to the cloth of my mother’s dress, the instruction clear:

“Mussa, hold this. Hold tight. Don’t let go.” We are fleeing Rwanda, crossing the border in the DRC, heading to Goma – my family a drop of water in a sea of people.

My parents are carrying my little sister and the luggage. They do not have enough hands for me.

A man pushes past.

I am three years old.

I let go.

I climb a little hill, scramble to the top, scanning faces, calling Mama! Mama!

Mama!

It is only later in the orphanage when they’re trying to trace my family that I realise that I do not know their names. Every other child on the hill was calling Mama too.

*

My daughters are four and two. It was a struggle at first, being a father, having not had my own father to teach me how to do it, but I’m getting better now.

One thing I make sure is that they know my name. I make them practice it. I wake them up, ask them, what is my name?

Mussa, they say, Mussa Uwitonze.

It used to be that it was a mark of disrespect in Rwanda to call your parents by their name, but not . I want them always, always to be able to find me.

I teach them ‘Mussa’, not ‘Samuel’, the Roman Catholic name I was given in the orphanage. Mussa is a Muslim name. I cannot remember my parents’ faces, but I remember the call to prayer, waking up, going with them to the first of the five daily prayers.

So my children call me Mussa and with that name they remember their father. And I remember mine.